Population: 173,759 (in 1901)

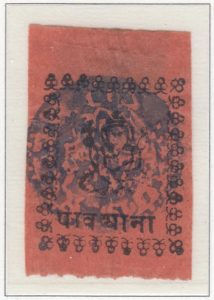

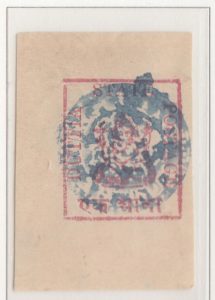

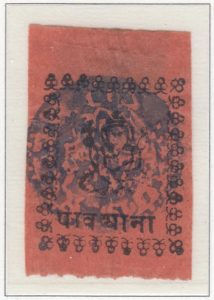

Duttia (or Datia) was a princely state in the Bundelkhand Agency in Central India (presently part of the state of Madhya Pradesh). The first stamps were issued in 1894(?) – 1896 during the reign of Maharaja Lokendra Bhawani Singh, who ruled the state from 1857 – 1907.

The stamps were type set, imperforate and without gum. They were hand stamped with a circular, control in blue. Specialists theorize that they were issued either singly or in horizontal strips. Gibbons also notes rectangular labels consisting of a set of four labels, possibly issued in 1893, that some students regard as the first issues.

Click here to see all stamps from Duttia in this exhibition.

History

Duttia was a small princely state, ruled by (Hindu) Rajputs. It was under the control of the Maratha (Hindu) empire until 1802. That year marked the Treaty of Bassein between the Maratha Peshwa and the Britains, ceding control of Duttia and other territories in the area. Duttia acceded to India in 1947, ultimately becoming part of the state of Madhya Pradesh.

The final two Maharaja Raja Lokendras, and, in particular, the last, were not held in high regard by the British. Bhawani Bahdadur (ruling 1857-1907), who issued the first stamps, had, according to the British, objected to, and neglected, the “English” education of his heir, and had consistently mismanaged his realm.

Locally educated and inadequately, at least by British standards, prepared, the heir, Govind Singh, promptly got into trouble upon inheriting the throne in 1907. Ten members of a highly placed family had been forced, or extorted, into suicide-murder, and the British, upon investigation, found that this was not an isolated incident. In 1910, the British forced Govind Singh into exile, using the opportunity to make him more “manly” through a hunting trip in Africa, as well as experience in such sports as cricket. Govind was allowed to return, with constraints, only to reexperience bouts of drunkenness, licentiousness, and “deviant” sexual practices.

The maharajah was returned to rule in 1914, and restrictions were lifted in late 1915, but by 1921, public drunkenness, evidence of frowned-upon sexual practices, and impetuous exercise of power made the British impose further restrictions on him. The first Maharini even requested that her son not have contact with his father. According to the British, he was surrounded by unqualified courtiers who cleaned out the treasury. Nevertheless, he retained his throne, with the dewan (chief Indian officer) and British political agent limiting his power.

With another bout of public drunkenness in 1941, again the British reviewed the situation. Again, he survived. His story closes in the 1940s, with two capable Muslim dewans managing state affairs. Unfortunately, the second, working in the period just before independence, experienced agitation for his removal because of his Muslim religion. The exasperated British accused Govind of inadequately protecting his officer.

Govind Singh died, miraculously having survived as ruler for 40 years. His is a story of the alcoholism and self-indulgence that characterized many rajas and maharajas, but equally of the reluctance of Indian princes to “dance to the fiddle” of British expectations. Indeed, in many ways Govind proved a popular ruler: in 1910; the protest of his removal was alarming enough that his departure had to be accompanied by British troops.

The maharajah was returned to rule in 1914, and restrictions were lifted in late 1915, but by 1921, public drunkenness, evidence of deviant sexual practices, and impetuous exercise of power made the British impose further restrictions on his power. The first Maharini even requested that her son not have contact with his father. According to the British, he was surrounded by unqualified courtiers who cleaned out the treasury. Nevertheless, he retained his throne, with the dewan (chief Indian officer) and British political agent further limiting his power.

With another bout of public drunkenness in 1941, again the British reviewed the situation. And again, he survived. His story closes in the 1940s, with two capable Muslim dewans managing state affairs. Unfortunately, the second, working in the period just before independence, experienced agitation for his removal because of his religion. The exasperated British accused Govind of inadequately protecting his officer.

Govind Singh died, miraculously having survived as ruler for 40 years. His is a story of the alcoholism and self-indulgence that characterized many rajas and maharajas, but equally of the reluctance of Indian princes to “dance to the fiddle” of British expectations. Indeed, in many ways Govind proved a popular ruler: in 1910, the popular protest was alarming enough that his departure had to be accompanied by British troops.

Duttia (Datia)

1893

Without Handstamp